The Minds Behind Freecell: How a Simple Card Game Became a Digital Icon

Anna | December 4, 2024

Freecell is more than just a game on your computer—it’s a clever blend of creativity, problem-solving, and a touch of serendipity. This legendary game owes its origins to a medical student with a knack for programming and a fascination with card games. Here’s the story of how Freecell transformed from a simple card game into the digital classic that’s hooked millions (and maybe stolen a few work hours along the way).

The Roots of Freecell

Long before Freecell graced computer screens, there were its ancestors: traditional card games like Napoleon in St. Helena, Eight Off, and Baker’s Game. Each brought something unique to the mix. Napoleon in St. Helena, documented in 1945, had strict rules about which cards could be placed in empty spaces. Then came Eight Off in 1949, with eight free cells (twice as many as Freecell) and a rule that only allowed kings in open columns.

The real breakthrough came in 1968 when American writer and mathematician Martin Gardner introduced Baker’s Game in his Scientific American column. It was a Solitaire variant that used four free cells and required building sequences by suit, making it more rigid and challenging than other games of its kind. However, it introduced the flexibility of allowing any card to occupy empty columns, which added a strategic twist. Though engaging, the game still lacked a certain flow. This would change a decade later in the hands of Paul Alfille.

Paul Alfille: The Mastermind of Freecell

Paul Henri Alfille might not be a household name, but if you’ve spent hours meticulously planning moves in Freecell, you’ve got him to thank—or blame. Born in the 1950s, Alfille had a mind wired for problem-solving. As a medical student at the University of Illinois in the 1970s, he wasn’t just cramming anatomy; he was exploring programming on the groundbreaking PLATO computer system.

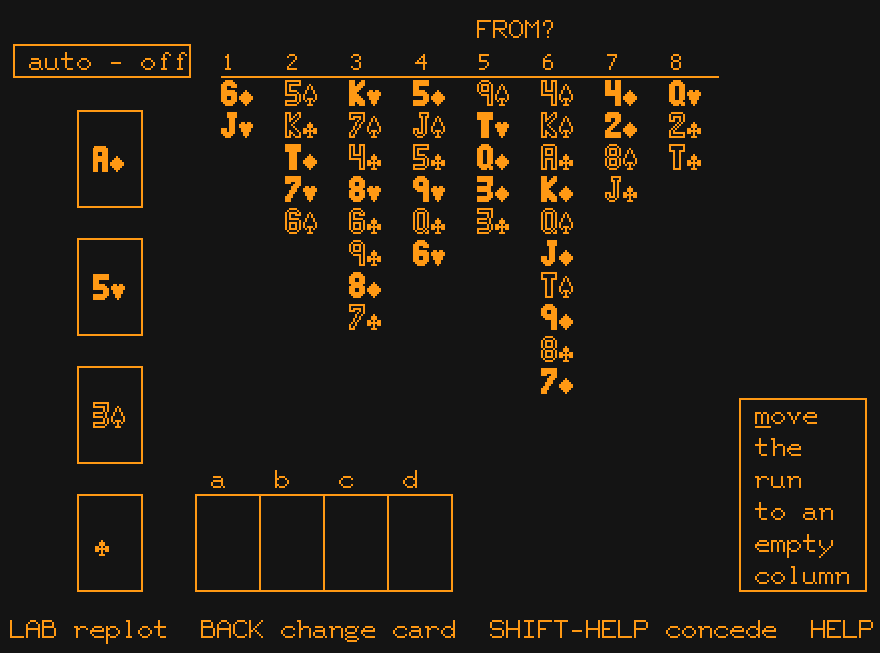

PLATO was more than just a computer—it was a tech playground. With its 512x512 monochrome display, it had just enough horsepower to support Alfille’s ambition: turning Baker’s Game into something smarter, sleeker, and, frankly, more fun. In 1978, Alfille coded the first computerized version of Freecell using PLATO’s TUTOR programming language.

He added a twist that would define Freecell: building sequences by alternating colors instead of by suit. This subtle change made the game not only easier to solve but far more strategic. For the first time, players could plan their moves without being at the mercy of bad luck.

His time on PLATO wasn’t all about games, though—it was also life-changing in a more personal way. Alfille’s passion for technology led him to meet Laurie Shapiro, a fellow medical student from the University of Connecticut, through the system. Their connection blossomed into one of the earliest examples of digital matchmaking and later, a marriage.

After creating Freecell, Alfille went on to become an anesthesiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital. While his medical career flourished, he never left his love of programming behind, continuing to explore technology in his personal and professional life. Freecell may have been a small part of his journey, but it’s a legacy that has brought joy (and a touch of frustration) to millions.

Jim Horne Brings Freecell to the Masses

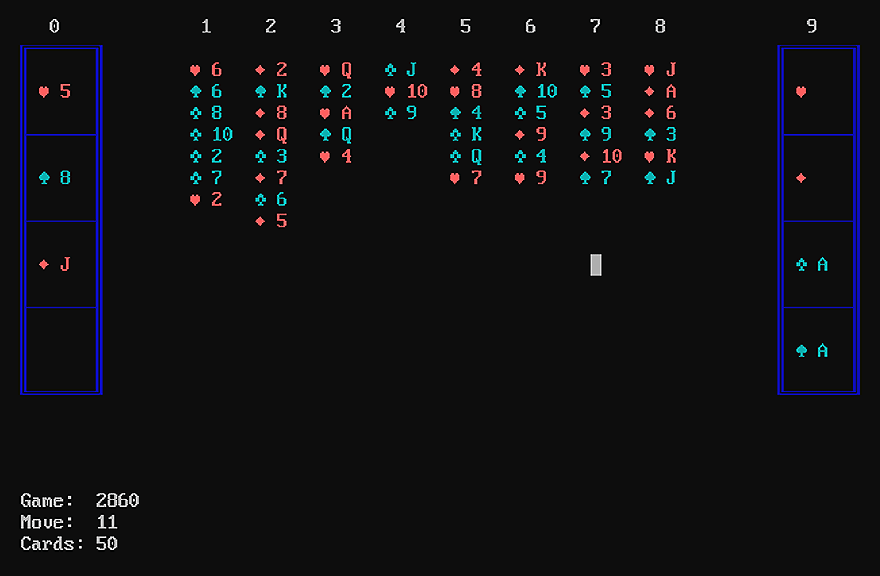

Despite its innovative design, Freecell remained a niche game until the late 1980s, when Jim Horne, a Canadian programmer at the University of Alberta, encountered it on the PLATO system. Fascinated by the game’s potential, Horne made it one of his first projects when he upgraded his TRS-80 to an IBM PC, creating the very first PC DOS version of Freecell in 1988. Like the PLATO version, this early version was text-based and used ASCII characters to represent card suits. This was all before the internet as we know it existed, so Horne shared his creation through CompuServe, a system where users could upload and download programs. Players could finally enjoy Freecell on their personal computers, even in this minimalist format.

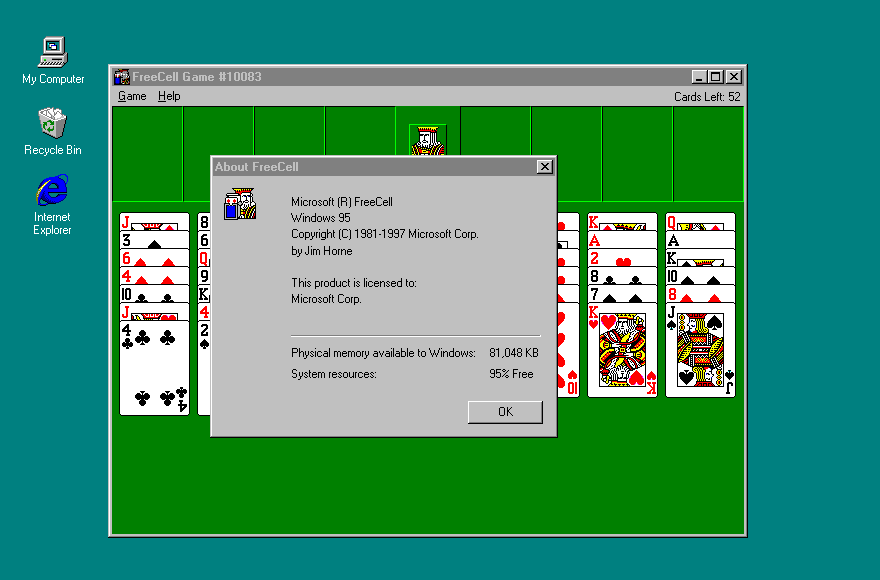

Horne’s big break came when he joined Microsoft in 1988. His boss at the time, Bill Gates, was worried that Windows wasn’t appealing enough to gamers, so he started collecting games created by employees and put the best 8 into a Windows Entertainment Pack. The Windows version in development at that time, Windows 3.0, already included the Klondike Solitaire game, developed by Wes Cherry. Horne borrowed its graphics and, in his spare time, created the first Windows version of Freecell, which earned its spot in the 1991 Microsoft Entertainment Pack Volume 2. While it gained some fans there, Freecell’s real rise to fame happened in 1995, when it became a built-in feature of Windows 95. Suddenly, millions of people around the world were discovering this addictively strategic game—and losing hours to it.

Windows 95 sold over 40 million copies in its first year, and with it, Freecell became more popular than even Word or Excel. It wasn’t just a way to kill time; it became a quiet challenge for solo players, offering endless opportunities to test their strategic thinking. Jim Horne’s original build stayed in place all the way through Windows XP. In more recent versions, the game was contracted out to another company, which created a fancier version with detailed graphics and sounds—but for many, the classic simplicity of Horne’s Freecell remains unmatched.

Why Freecell Sticks Around

What makes Freecell so special? It’s not just about luck—nearly every game is solvable if you’re clever enough. That solvability keeps players coming back, determined to crack even the toughest deals. Its simple rules make it easy for anyone to pick up, while the strategic depth ensures it never gets boring. It’s kind of like the perfect Solitaire game.

Jim Horne himself summed up its appeal perfectly: “It’s a great game because it seems to have some built-in psychology. When you first start, the games can be tricky, but as you get better, you find yourself winning more consistently. Soon you begin to get cocky, your concentration level drops, and you get slammed down. It’s nice relaxation, but if you relax just a little too much, you get stuck.”

And let’s not forget its incredible staying power. Freecell is more than 40 years old, yet it still feels fresh every time you play. Whether you’re a casual gamer or someone who geeks out over perfect win streaks, Freecell has something for you.